If I Weren't Here, I'd Want to Be: Reflections on a Successful Student Protest

Ashley Wurzbacher

Apr 14, 2013

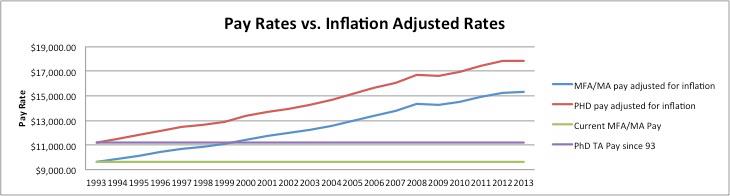

Last month my colleague Justine Post blogged about the early days of the protest that happened recently here at the University of Houston, in which graduate teaching fellows in the English department--many of us also students in the Creative Writing Program and editors for this journal--demanded that university administration take immediate action to adjust our unlivable wages, which had remained stagnant for twenty years. As Justine pointed out, teaching fellows here at UH were earning well below the poverty line ($9,600 for MFAs and $11,200 for PhDs) for teaching two courses per semester--the same teaching load that many of our full-time professors carry--and were paying approximately 18% of their salaries straight back to the university in mandatory fees. With no wage adjustments in two decades, our salaries were not competitive with those offered by most other graduate writing programs. TF salaries, unchanged since 1993 (click for larger image)

As teaching fellows, we are not assistants to other professors, but are the instructors of record for the courses we teach, most of which are part of the university's core curriculum. Our contracts obligate us to work only for the university, so those of us who took on (inevitable) second and third jobs in order to be able to pay our bills were technically in violation of our contracts and were unable to devote to our students and our studies the attention they deserved. Our writing was suffering, our students were suffering, and--I think it's fair to say--the well-being of our program was suffering.

So in early April, graduate students and faculty members in our Department, including many of the Gulf Coast editors, staged a four-day sit-in at University Chancellor Renu Khator's office.

TF salaries, unchanged since 1993 (click for larger image)

As teaching fellows, we are not assistants to other professors, but are the instructors of record for the courses we teach, most of which are part of the university's core curriculum. Our contracts obligate us to work only for the university, so those of us who took on (inevitable) second and third jobs in order to be able to pay our bills were technically in violation of our contracts and were unable to devote to our students and our studies the attention they deserved. Our writing was suffering, our students were suffering, and--I think it's fair to say--the well-being of our program was suffering.

So in early April, graduate students and faculty members in our Department, including many of the Gulf Coast editors, staged a four-day sit-in at University Chancellor Renu Khator's office.

We plastered the campus with fliers and our signature highlighter-yellow ribbons, accumulated over a thousand Facebook followers, and received coverage in a number of local and national publications.

We collectively resolved not to back down until we received a concrete wage adjustment offer from the administration. Our faculty joined us on the Chancellor's floor, brought us lunch at noon, and wrote about our efforts. And eventually, we succeeded.

We plastered the campus with fliers and our signature highlighter-yellow ribbons, accumulated over a thousand Facebook followers, and received coverage in a number of local and national publications.

We collectively resolved not to back down until we received a concrete wage adjustment offer from the administration. Our faculty joined us on the Chancellor's floor, brought us lunch at noon, and wrote about our efforts. And eventually, we succeeded.

Our sit-in ended with a meeting with the chancellor, provost, and dean of the College of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences. At that meeting, Chancellor Khator proved herself a true Tier One administrator when she allocated one million dollars of the university's student success budget to address the problem of Teaching Fellow salaries. Our dean later freed up another $250,000, and these funds were subsequently divided among departments within the college whose teaching fellows teach classes that are part of the university's core curriculum. Since many of those classes are English classes, our department's allocation was enough to raise our meager salaries by 55-60 percent, beginning in the next academic year.

It was mind-boggling being in that room when Chancellor Khator waved her metaphorical magic wand to make our problems--many of them, anyway--disappear. Our faculty had been advocating for our interests for years, but until we all joined forces and sat on that office floor, no one had been able to penetrate the upper echelons of the university; and yet once we were there, once we'd forced our way in, everything seemed so simple. It wasn't, of course; but it seemed that way.

Our sit-in ended with a meeting with the chancellor, provost, and dean of the College of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences. At that meeting, Chancellor Khator proved herself a true Tier One administrator when she allocated one million dollars of the university's student success budget to address the problem of Teaching Fellow salaries. Our dean later freed up another $250,000, and these funds were subsequently divided among departments within the college whose teaching fellows teach classes that are part of the university's core curriculum. Since many of those classes are English classes, our department's allocation was enough to raise our meager salaries by 55-60 percent, beginning in the next academic year.

It was mind-boggling being in that room when Chancellor Khator waved her metaphorical magic wand to make our problems--many of them, anyway--disappear. Our faculty had been advocating for our interests for years, but until we all joined forces and sat on that office floor, no one had been able to penetrate the upper echelons of the university; and yet once we were there, once we'd forced our way in, everything seemed so simple. It wasn't, of course; but it seemed that way.

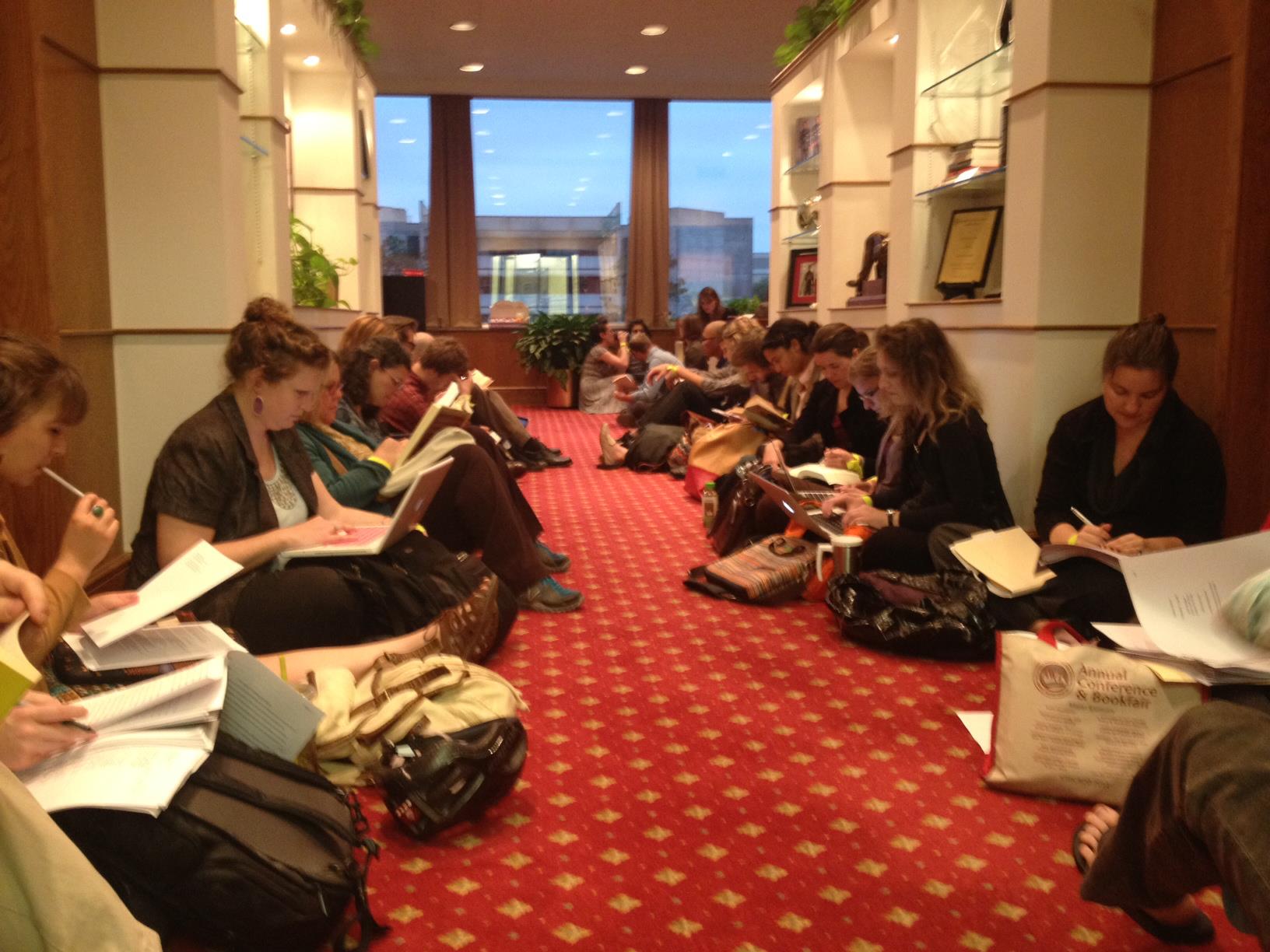

Department faculty sitting-in with English teaching fellows.

Yet in our meeting with the chancellor, she insisted that in spite of all we'd gained, we'd also lost a great deal in the process of gaining it. We'd made a scene, sitting on her floor, attracting media attention. We had, in her estimation, done six or seven years' worth of damage to our program's good name.

I'm not so sure that's true.

Because the truth is that if I weren't here already, I'd want to be. When I think back to where I was at the time I applied to PhD programs, working as an adjunct at the University of Montana in Missoula, barely scraping by and facing many of the same problems and injustices that we've been fighting here at UH, I know that I'd want to go where the students pulled their noses out of their books and took collective and direct action to improve their working conditions. I'd want to go where the professors--some of the finest and most distinguished writers around--sat on the floor of the president's office in solidarity with their students without a second thought. I'd want to go where activism is not a pose, but a reality. I can't say it any better than Justine did in her past post:

Department faculty sitting-in with English teaching fellows.

Yet in our meeting with the chancellor, she insisted that in spite of all we'd gained, we'd also lost a great deal in the process of gaining it. We'd made a scene, sitting on her floor, attracting media attention. We had, in her estimation, done six or seven years' worth of damage to our program's good name.

I'm not so sure that's true.

Because the truth is that if I weren't here already, I'd want to be. When I think back to where I was at the time I applied to PhD programs, working as an adjunct at the University of Montana in Missoula, barely scraping by and facing many of the same problems and injustices that we've been fighting here at UH, I know that I'd want to go where the students pulled their noses out of their books and took collective and direct action to improve their working conditions. I'd want to go where the professors--some of the finest and most distinguished writers around--sat on the floor of the president's office in solidarity with their students without a second thought. I'd want to go where activism is not a pose, but a reality. I can't say it any better than Justine did in her past post:

For those of us who write, our voices are our art. We write loud and noisy prose. We write cutting poems. We write sentences that make you feel full of the world. We enjamb our hearts out in iambic pentameter. We say everything you ever wanted to say, but couldn't or didn't. In the confines and safety of a piece of paper, we are revolutionary. So, why do we become quiet and humble and shy when it's time to ask for what we need?We refused to be quiet, humble, and shy. We were loud, proud, and bold, and in being so we changed the culture of our program and improved our own lives, the lives of graduate students in other departments who also benefitted from the new budget allocation, and the lives of our students, who will now be able to enjoy our full attention in ways that they couldn't when we had to work two or three outside jobs just to survive.

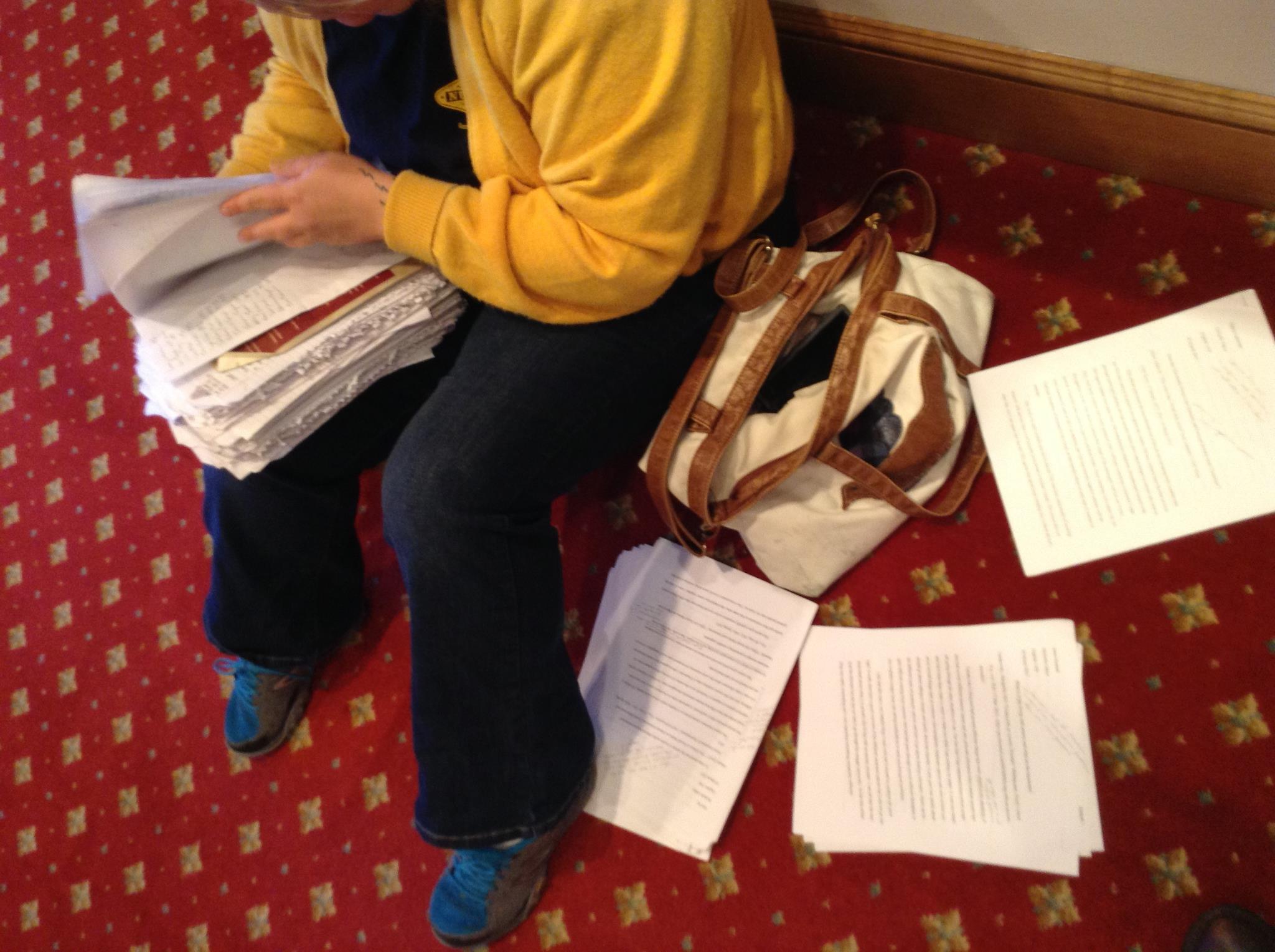

Gulf Coast poetry editor Michelle Oakes grades papers at the sit-in.

And Justine is right to emphasize the connection that exists--or that should exist--between our art and our actions. The work that we do as writers, and indeed the very act of reading, requires us to put ourselves into others' shoes, to imagine others' experiences, to create worlds. It's this unending project of imagination and identification that fuels us creatively. We shouldn't let this sensibility limit itself to the words we put on the page. And we should not accept that the fact that we love what we do--sharing the power of the written word with our students--somehow means that we should do it as charity and not expect fair compensation.

Gulf Coast poetry editor Michelle Oakes grades papers at the sit-in.

And Justine is right to emphasize the connection that exists--or that should exist--between our art and our actions. The work that we do as writers, and indeed the very act of reading, requires us to put ourselves into others' shoes, to imagine others' experiences, to create worlds. It's this unending project of imagination and identification that fuels us creatively. We shouldn't let this sensibility limit itself to the words we put on the page. And we should not accept that the fact that we love what we do--sharing the power of the written word with our students--somehow means that we should do it as charity and not expect fair compensation.

|

Comments (0)

Add a Comment